Gladiator Simulator

by Richard in14 Apr 2020

Recently the following remark was made by user ajacian81 on statistics question-and-answer site crossvalidated.

Side note: In an uneven fight, 2 v 1 vs 20 v 10, I believe the 1 fighter vs 2 has a better probability of winning than 10 over 20.

I became curious as to whether this is true, and if so, why?

Model

To begin with, we need a way of modelling the situation of a fight between two sides.

Our model had better not be deterministic, or else we can decide who will win by counting how many fighters are on each side.

Let us suppose side $A$ has $a$ fighters and side $B$ has $b$ fighters. Each fighter simultaneously picks an opponent on the opposite side. They win against this opponent with probability $p$. Suppose all these mini-fights happen independently.

Then the number of fighters on side $A$ defeated by side $B$ is a binomial $(b, p)$ random variable, and vice-versa.

Either we can end the fight here and send each side home to lick their wounds, or continue to the death in gladitorial style.

Continuing to the death gives the following model.

while ((a > 0) & (b > 0)){

a_next <- a - rbinom(1, b, p)

b_next <- b - rbinom(1, a, p)

a <- a_next

b <- b_next

}

Simulations reveal that, in a 1 versus 2 battle with $a=1$, $b=2$, $p=0.5$, the weaker side wins just under 5% of the time, but in a 10 versus 20 battle, the weaker side has practically no chance of winning (see below) so ajacian81 was correct!

The Survivors

I next became interested in how many survivors there would be on the larger side at the end of the $a=10$, $b=20$, $p=0.5$ battle.

The expected number of losses in the first round is 5, so I expect there will be about 15 survivors.

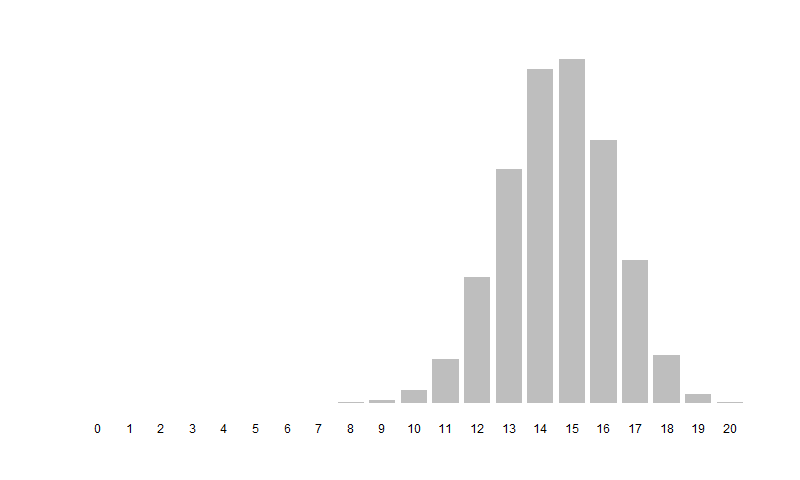

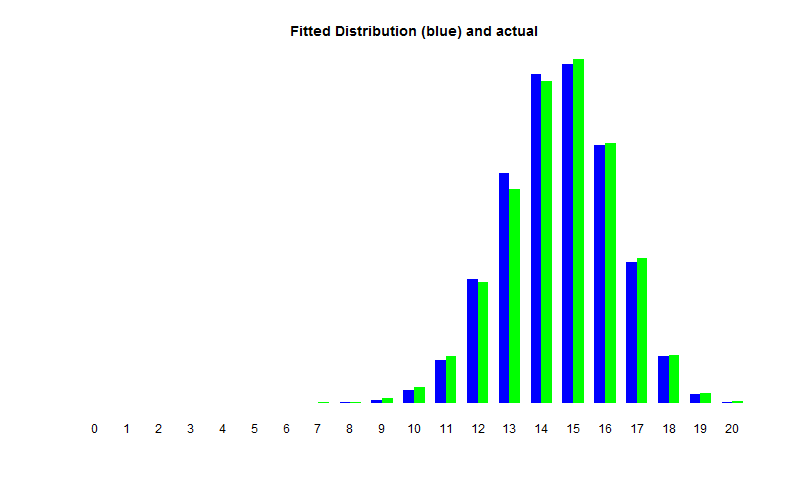

In fact, the average number of survivors is 14.56 and the distribution of survivors looks like the graph below, which shows the results from 10000 model runs.

I was curious about whether it was possible to describe this distribution analytically.

It turns out that it is very unlikely for the fight to go on for longer than two turns, so the number of survivors can be approximated by the number of survivors after two rounds, which is

\[b - \mathrm{Bin}(a, p) - X\]where $\mathrm{Bin}(a, p)$ is a binomial random variable, and $X$ is defined as $\mathrm{Bin}(a - \mathrm{Bin}(b, p), p)$ if $a - \mathrm{Bin}(b, p) > 0$, and $0$ otherwise.

By a highly questionable calculation, I found that $X$ was approximately a $\mathrm{Poisson}(\sqrt{5/8\pi})$ random variable.

Round One

When the battle starts with $a=b$, it is likely that there will be many more than $2$ rounds, so the above approximation is wrong. This led me to consider what happens if the battle is not fought to the death, but ends after one round, with the winning side being whoever has more gladiators left.

Also, we can generalise to the situation where each fighter on side $B$ has a probability $q$, of defeating a fighter on side $A$, where maybe $q \neq p$.

Now side $B$ wins if

\[a - \mathrm{Bin}(b, q) < b - \mathrm{Bin(a,p)}\]and, if we are allowed to use the normal approximation to the binomial, the probability of side $B$ winning is

\[1 - \Phi\left(\frac{(1+p)a - (1+q)b}{\sqrt{bq(1-q) + ap(1-p)}}\right)\]where $\Phi$ is the normal cdf.

When $p=q$ and $a=2b$, we are in the situation of ajacian81 again, and the thing inside the $\Phi$ is a constant times $\sqrt{b}$. This confirms that the more fighters there are, the higher the probability of a win for the stronger side.

The Tipping Point

In general, the first round of the battle is decided by the expression

\[(1+p)a - (1+q)b\]in the sense that the sign of this expression determines which side is favoured to win the first round. For example, if $135$ gladiators with a hit probability of $0.4$ fight $100$ gladiators with a hit probability of $0.9$, both sides are more or less equally likely to have the majority of gladiators left after the first round. (However, if they fought to the death, then the $100$ gladiators would almost certainly win.)

Lanchester’s Law

I would be surprised if this model had not been studied before, as it seems very natural and simple. The closest thing I could find is the deterministic version

\[\begin{align*} a_{n+1} &= a_n - qb_n\\ b_{n+1} &= b_n - pa_n \end{align*}\]which is known as the Hughes Salvo Equation. The continuous analogue of this is more famous, and is known as Lanchester’s Equation. The solution of this equation leads to Lanchester’s Law, which states that the quantity

\[pa^2 - qb^2\]is a constant. If the two sides fight to the death, the winning side will be whichever has the larger value of $pa^2$ or $qb^2$. There is a nice proof in a review article by N. MacKay.

Applying this to the gladiator model does indeed suggest that the side with the higher probability of winning a fight to the death is determined by whoever has the bigger value of $pa^2$.

There is also a relationship between Lanchester’s Law and the ‘round one’ result from above. From Lanchester’s Law, it follows that the winner is whoever has the higher value of $\sqrt{p}a - \sqrt{q}b$, and $\sqrt{x} \approxeq (1+x)/2$, but only if $x$ is close to $1$.

From various numerical experiments I suspect, but cannot prove, that what happens in the gladiator model is that either the fight is almost perfectly balanced, or it is a runaway victory for one side or the other (in the sense that the stronger side, in the sense of Lanchester’s Law, wins almost every time.)