Death on Mount Everest, Regression to the Mean, and the Gambler's Fallacy

by Richard in02 Dec 2024

Introduction

A story on outsideonline.com notes that the number of deaths on Everest in the 2024 season has fallen from a record high in 2023. There are many possible reasons for this. It could be new safety measures, new rules for climbers, better weather… Or, possibly, no reason at all.

Here’s another seemingly unrelated question. Why do rich parents tend to have (relatively) poorer children? Why are the children of rich people rich, but not as rich, as their parents? It could be because inheritances often have to be split among many children, or because children who grow up among wealth become soft and lazy, or because of inheritance taxes.

But there is another explanation, too. One which is so revoltingly simple that people often find it repugnant.

Regression to the Mean

It’s a general fact that, if you take samples at random from a population, an unusually high value will tend to be followed by a smaller value. Why? Well, suppose you sample a value, and it happens to be at the 90th percentile. That means that there’s a 90% chance that a random sample from your population is less than it. In particular, there’s a 90% chance that the next value is less than it. That’s all!

To see it even more clearly, think about rolling a six-sided die. What happens if you roll a 6? Well, the next number is equally likely to be any of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or 6. So there’s a 5 in 6 chance that the next roll will be lower than 6.

This rather obvious fact is called regression to the mean, and it can explain all sorts of unrelated phenomena. For example, suppose we were living in some kind of Rawlsian society in which wealth was assigned to people at random when they were born. Then, despite the fact that there is no inheritance, you would still expect the children of rich parents to be poorer than their parents in general, by pure mathematics. No explanation required!

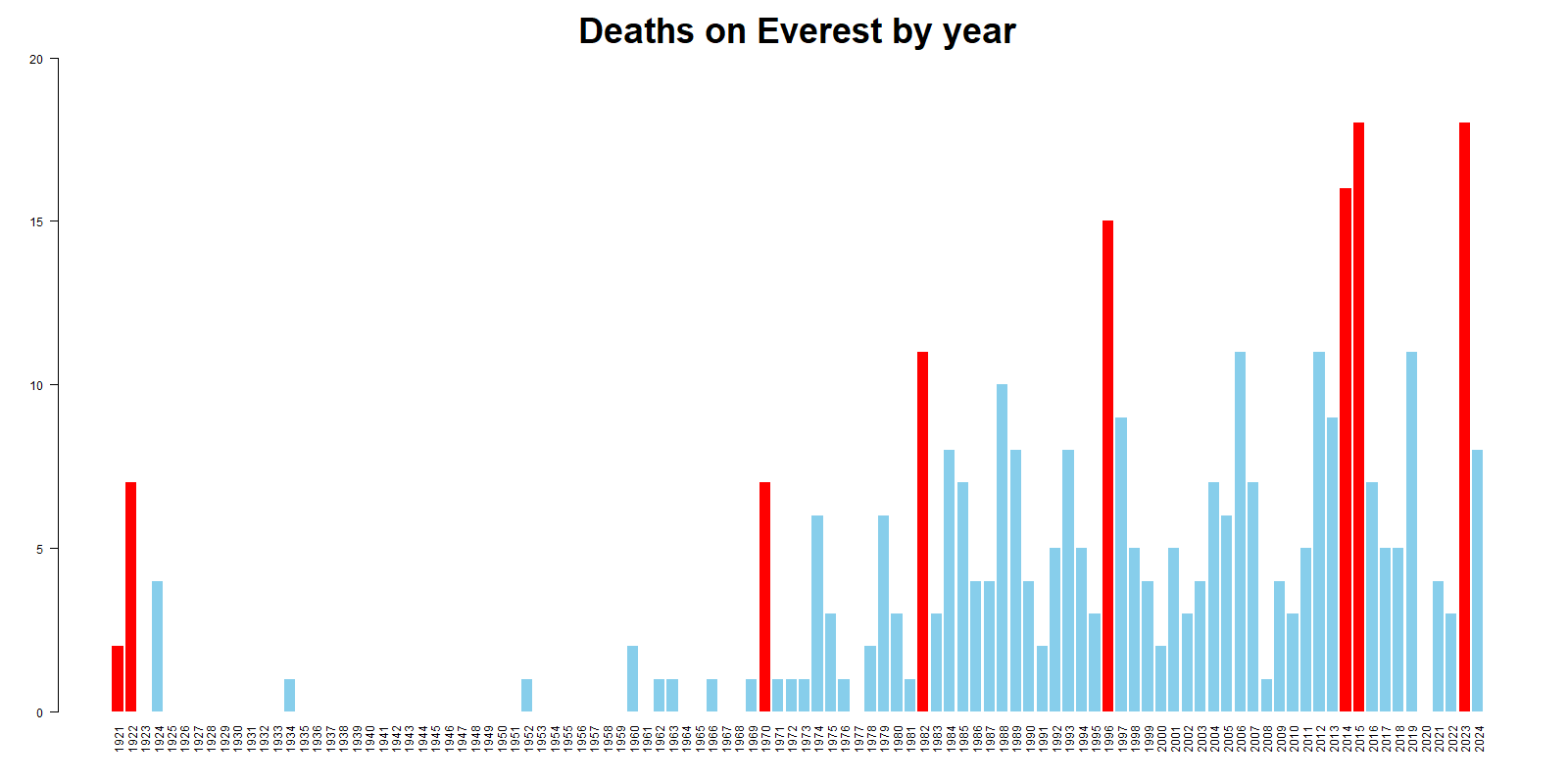

Let’s look at a graph of deaths on Everest in every year from 1921 to 2024. The red bars show the years in which the number of deaths was equal or higher to the highest ever recorded value. In 6 cases out of 8, the next year was followed by a lower number of deaths. It doesn’t matter whether the weather was better or the mountain was safer. It just happened.

This kind of situation often occurs in real life. The story goes: there is an unusally high count of some undesirable event. People get upset. Some sort of safety measure or intervention is put in place. Next year/month/week/season, the undesirable event happens less often. The people who put the intervention in place are heaped with praise. But did they really do anything? It’s not always so clear.

But what if there isn’t a mean?

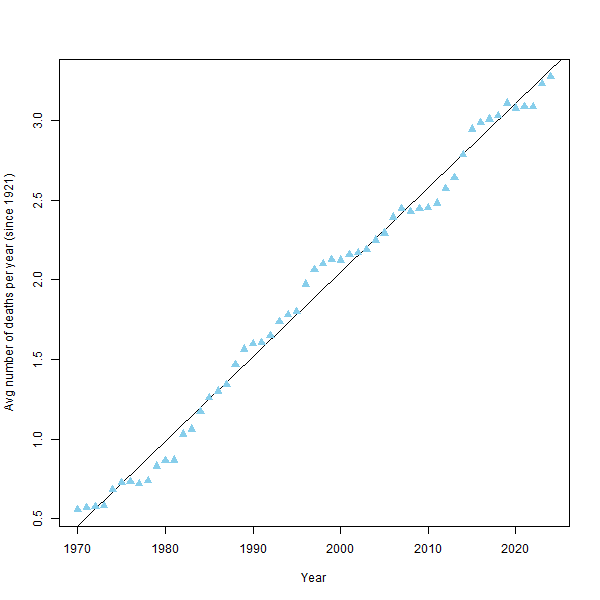

In the case of Everest deaths, however, perhaps it’s not really fair to speak about regression to the mean. If you calculate average deaths per year measured since 1921 and make a graph for each year, you can see a steady (in fact, surprisingly linear) increase since 1970, probably related to the increased number of people who are climbing the mountain. So perhaps regression to the mean doesn’t apply? Perhaps there isn’t a mean?

I think this is a reasonable objection; a lot of observed stochastic processes in real life don’t have a mean. But this doesn’t mean that regression to the mean doesn’t happen. For example, suppose we model deaths on Everest with a Poisson process with a rate $\lambda(t)$ which increases over time. Provided that the increase is slow enough, we still expect that an unusally high number of deaths in one year will be followed by a lower number of deaths in the next year. We’re sampling from a distribution which shifted a little bit, but not too much.

But what about the Gambler’s Fallacy?

Here’s where it gets confusing. When I was teaching statistics, I always stressed that coins and dice don’t have a memory. If you flip ten heads in a row, you don’t have a higher probability of getting a tail on the next flip to “balance things out” by the “law of averages”. The probability of a tail on the next flip is still $1/2$. Everyone who has taken statistics knows that.

But wait! The Gambler’s Fallacy says that you can’t predict the next observation in a sequence. But regression to the mean says that you can, sort of. Isn’t that a contradiction?

Well no, not really. The Gambler’s Fallacy is a statement about the whole history of a stochastic process. It says that, conditional on what we have already observed, we expect a certain thing to be true (for example, a higher chance of a tail after ten heads). And it’s wrong. Regression to the mean is a statement about the next observation (or any observation) given the last observation, regardless of what happened before. And it’s right (although, just to confuse the issue even more, in the coin-flipping case regression to the mean tells us nothing about the next flip because there are only two possible outcomes. And the Gambler’s Fallacy would be correct if we were, for example, drawing cards from a finite pile of cards marked “heads” and “tails” instead of flipping a coin, which is actually not so far from the truth in many real-life situations. For example, if you pick 10 people from the US population and they are all Republicans, the next person you pick is slightly more likely to be a Democrat.)

So, although it’s worthwhile to look for reasons why the number of deaths on Everest is going down, it’s also worth considering whether it happened for no reason at all.