Paper Plates and Interest Rates

by Richard in23 Dec 2024

I recently finished working through The Applied Theory of Price by McCloskey. This textbook teaches price theory in a very interactive way with lots of questions and answers. The questions are often surprising, counter-intuitive, or provocative, which gives the book an unusual liveliness (which may explain why the author has made the book freely available. Apparently it was considered too controversial to be reprinted.)

Here’s an example (problem 3.4.3):

True or False: It costs John 1 cent worth of time and trouble to fasten his seat belt on each trip in his car; putting on his seat belt reduces his risk of dying in a crash from 1 in 2 million on each trip to zero; and John’s utility curve of income is a straight line. Therefore, if John were just indifferent between fastening the seat belt and not fastening it, he would be willing to be shot one year from now for $20,000.

Or how about problem 8.1.8:

True or False: On grounds of efficiency we should not acquire a president by election: The office should be for sale to the highest bidder.

Today I want to consider a different problem from Section 26.1.

True or False: A fall in the real interest rate will increase the value of china plates relative to paper plates.

This is a typical head-scratcher from the book. At first, it seems that dinner plates have nothing to do with interest rates. But the proposed answer is “True”. The reasoning is based on the formula for the present value of a perpetuity. If $R$ is the value of the use of the plate and $i$ is the interest rate, then the present value of a plate that lasts forever is $R/i$, whereas the present value of a plate that lasts for one year is $R/(1+i)$, so a fall in the interest rate $i$ translates into an increase in the value of the everlasting plate relative to the paper plate.

The book goes on to state that, in general, “a fall in the interest rate favours the use of relatively durable things relative to flimsy things”. This is later used to explain why railroads in the 19th century US were built in a less durable way than those in Britain. All other things being equal, higher interest rates in the US led to a higher demand for flimsy railroads.

This all sounded a bit far-fetched to me, so I couldn’t resist testing it out with some data.

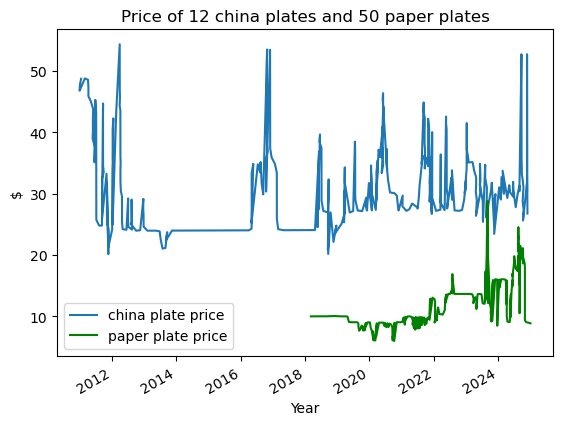

Unfortunately, it was not easy to find publically-available data on the historical prices of plates. I used camelcamelcamel to compare the plates with the longest Amazon price histories I could find and with sizes as close as possible (the plates have to be close substitutes). For china plates, this was 10 Strawberry Street 10.5” Catering Round Dinner Plate, Set of 12 , White with a price history going back to 2011, and for paper plates it was Glad 10 Inch Round Paper Plates 50 Count - Heavy Duty Round Disposable Plates for Parties - Sturdy, Soak Proof, Microwave Safe Plates - Large, Thick Plates for Dinner - Bulk Microwavable Paper Plates with a history going back to 2018. The data cannot be downloaded directly, so I used web plot digitizer to extract it.

The price series looked like this:

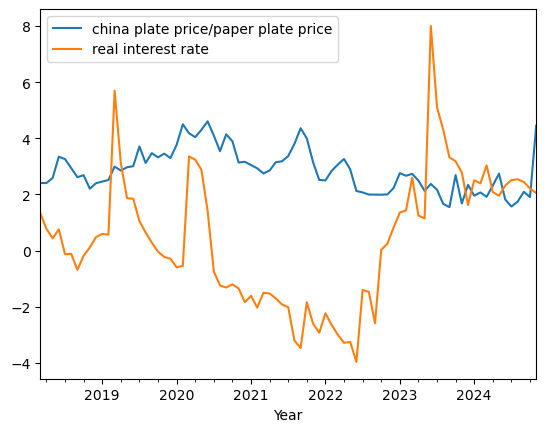

For estimates of the real interest rate in the US, I used time series data from the St. Louis Fed.

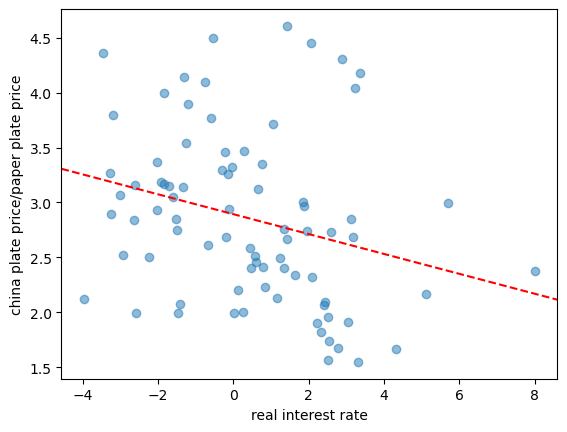

It turned out that there was a negative correlation of $-0.27$ between the real interest rate and the price of china plates relative to paper plates (numerically speaking, it was statistically significant, but it’s not reasonable to talk of statistical significance here because the prices at subsequent time points are not independent).

So this ad hoc experiment does support the true/false assertion in the book. But, digging a little deeper, it seems that the formulas $R/i$ and $R/(i+1)$ don’t predict the difference in price observed between china plates and paper plates. For one thing, the formulas assume that the interest rate $i$ is stable over time. For another, the formula for the present value of a perpetuity doesn’t even make sense if the real rate $i$ is negative! If $i$ is negative then the present value of the perpetuity should be $\infty$ (this mathematical fact may have real world implications for long-term bonds too).

Overall, I think the best you can say is that it’s plausible that a fall in real interest rates really does increase the price of china plates relative to paper plates, and in general of long-lasting things relative to breakable things. We’ve been living through a period of low interest rates from 2008 until recently, so perhaps that explains why everything seems to be so poorly-engineered these days? Perhaps there’s even a gloomy lesson to be learned about inequality? Perhaps low interest rates cause the prices of durable things to soar out of reach, forcing the poor to substitute them with temporary things? Perhaps, as recent research from Duke University suggests, low real rates can behave like a poverty tax?